Stages Of Fasting: What To Expect In The Short & Long Term

Fasting is a practice that dates back thousands of years and is still a staple across many religions and cultures.

More recently, variations of fasting like intermittent fasting, circadian rhythm fasting, and time-restricted feeding have been studied for their potential health effects, with some research indicating that fasting could even help you live longer1, ward off chronic disease, and rev up weight loss and fat burning.

Advertisement

In this article, we'll take an in-depth look at the science behind each stage of fasting, along with some expert-backed tips on what to do to maximize each one.

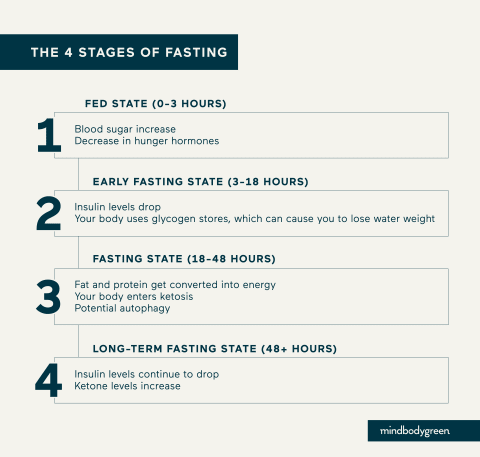

The four stages of fasting.

The physical changes that your body goes through during a fast can be divided into four stages:

- Stage 1: Fed state (0-3 hours)

- Stage 2: Early fasting state (3-18 hours)

- Stage 3: Fasting state (18-48 hours)

- Stage 4: Long-term fasting state (48+ hours)

Advertisement

Within the first 18 hours after eating, your body moves through two of these stages, including the fed state and early fasting state.

Most popular forms of time-restricted eating (TRE), such as 16:8 or 18:6 fasts, also cycle between these two stages2 of fasting.

Fed state (0-3 hours)

The fed state is the first stage of fasting, which occurs within the first three to four hours2 after you eat.

During this period, your blood glucose levels increase as your body digests and absorbs your meal. This leads to a rise in insulin secretion, which helps regulate blood sugar levels to provide cells throughout the body with a steady stream of energy.

There's a shift in the levels of a few other hormones around this point as well. For instance, ghrelin3—a hormone that makes you feel hungry—tends to drop one to two hours after eating. On the other hand, leptin levels increase4 during the fed state, making you feel full.

While this all may seem complex and convoluted, it's actually a simple process that occurs every single day after you eat (when you're not fasting, of course). Basically, all of these dips and spikes in hormone levels are responsible for powering your body and keeping you feeling full between meals.

Advertisement

Early fasting state (3-18 hours)

Around three hours or so after your meal, your body shifts2 to the early fasting state, which lasts until about 18 hours after the beginning of your fast.

During this stage, your pancreas begins secreting higher amounts of a hormone called glucagon, which helps prevent blood sugar levels from dipping too low. Additionally, insulin levels drop5 and the body begins using glycogen—a form of glucose that's stored in the liver—as an alternative source of energy.

If you've ever noticed the weight seemingly melt right off after a day of fasting, glycogen might be behind it. Every gram of glycogen6 is connected to 3 grams of water, meaning that those glycogen stores are often the culprit for water weight.

Once your glycogen stores are depleted toward the end of this stage, your body starts looking for other sources of fuel and may even start breaking down proteins and fats.

This process is facilitated7 by a whole host of hormones, including glucagon, epinephrine, growth hormone, and cortisol, all of which are increased during fasting. It's also partially responsible for the fat-burning benefits of fasting.

After around 18 hours, your body enters the fasting state, followed by the long-term fasting state (also aptly named the starvation state). This is more common with longer fasts, including alternate-day fasts or periodic fasts, some of which can last up to 48 hours.

Fasting state (18-48 hours)

The fasting state occurs around 18 hours after the beginning of your fast and can last for up to two days. Because your glycogen stores have most likely been completely depleted by this point, your body has probably already started breaking down stored fats (aka triglycerides) and proteins and converting them into energy.

To dive right into the nitty-gritty details, this is all done using a process called lipolysis5, which relies on a specific enzyme known as hormone-sensitive lipase. It also results in the production of ketones8, which are chemicals that help supply extra energy1 to tissues throughout the body, including the brain.

Over time, this causes your body to enter ketosis, a metabolic state in which your body relies on fat instead of sugar9 as its main source of energy. This can also be achieved without fasting, using very low-carb diets like keto.

This basically means that your body is being powered by ketones instead of carbs because you're not eating.

How long it takes you to enter ketosis can vary depending on many factors10, including your age, activity level, and metabolism. It can also be influenced by your usual diet. For instance, if sugary snacks, sweets, and soda are a staple in your daily diet, it may take you a little longer to completely deplete your glycogen stores.

Interestingly, some research also suggests that this stage of fasting may trigger autophagy, a catabolic process used to clean out damaged cells and replace them with healthy new ones. In fact, one study showed that markers of autophagy were detected11 in white blood cells after just 24 hours of fasting. Plus, levels of mTOR, a protein that blocks autophagy12, are also decreased during this stage.

"Research suggests that autophagy13 may have a protective effect against aging, cancer, and other diseases," explains Humaira Jamshed, Ph.D., a nutrition and TRE researcher at the Dhanani School of Science and Engineering.

Impressively enough, some researchers even believe that enhancing autophagy could extend the life span14 and slow signs of aging.

Advertisement

Long-term fasting state (48+ hours)

The final stage of fasting is known as the long-term fasting state, or the starvation state. Insulin levels slowly continue to drop2 during this phase, while ketone levels steadily increase. Ketones serve as the body's main source of energy, and the breakdown of amino acids (aka protein) from the muscle cells is reduced to help preserve muscle mass.

Several other benefits have been reported in long-term, medically supervised fasts. For example, one 2019 study15 found that prolonged fasts ranging from four to 21 days caused a reduction in blood sugar, body weight, blood pressure, and belly fat, along with decreased hunger and improved feelings of physical and emotional well-being.

However, keep in mind that long-term fasts are definitely not recommended for everyone and can be downright dangerous16 if not done correctly. Therefore, this type of fasting should only be done under the guidance and supervision of a trusted health care professional.

Advertisement

Exercising during a fast.

Just as important as what you eat after you exercise is what you eat (or don't eat) before. In fact, multiple studies suggest that fasting can influence your workout performance and could either help or hinder your performance in the gym.

According to a review published in the Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, exercising after an overnight fast could offer a few notable benefits. In particular, the review concluded that it may help promote fat burning17, reduce calorie intake throughout the day, and activate certain pathways that influence metabolism in the muscles and fat cells.

On the other hand, a massive review of 46 studies reported that while eating before exercise may not impact short aerobic workouts, it could actually enhance performance18 during longer workouts.

Kelsey Gabel, R.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor and intermittent fasting researcher at the University of Illinois at Chicago, notes that scheduling your eating window around the times when you exercise may be the easiest option when it comes to intermittent fasting.

"There have been a few studies19 in alternate-day fasting combined with exercise," says Gabel. "Participants stated that fasting did not interfere with their ability to exercise, but listening to your body is always important."

Breaking a fast.

When it's time to break your fast, Jamshed recommends opting for nutrient-dense foods, which can help prevent overeating and keep blood sugar levels balanced. Ideally, it's best to stick to whole foods and aim for a good balance of carbs, heart-healthy fats, and healthy proteins in your meal.

For longer fasts, limiting your portion sizes and avoiding large meals or foods that are heavy or difficult to digest might also be a good idea initially to avoid overloading your digestive system. Lighter foods like soups, cooked vegetables, and lean proteins can help ease your body back into the swing of things after breaking your fast.

In addition to supporting healthy blood sugar levels, getting plenty of protein in your diet both before and after fasting is crucial for maintaining muscle mass20. Staying hydrated can also help keep your immune system working efficiently and ensure that you're able to maximize the potential benefits of fasting.

When to stop fasting.

Fasting is not recommended for certain groups, including children, adolescents, people with a history of eating disorders, and individuals who are underweight. "Safety has also not been evaluated in pregnant or lactating individuals or individuals over the age of 70," adds Gabel.

Gabel advises speaking to a doctor or dietitian before starting a fasting regimen if you are taking medications or have any other health complications. She also recommends breaking your fast if you experience symptoms of low blood sugar, such as a fast heartbeat, shaking, or dizziness.

According to Jamshed, it may also be best to break your fast if you experience other serious symptoms like headaches or migraines, nausea, vomiting, extreme hunger, weakness, fainting, or loss of consciousness. "It's important to listen to your body and break the fast if you experience any of these symptoms, or if you feel unwell in any way," she adds.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a 72-hour fast do to your body?

Prolonged fasting can cause your body to enter ketosis, which occurs when your body uses fat as its main source of energy instead of sugar. A 72-hour fast may also promote autophagy and alter levels of certain hormones, such as insulin.

What is the ketosis stage of fasting?

Ketosis occurs when your body begins using fat as its primary source of energy rather than carbohydrates or sugar. Although this typically occurs during the fasting state, many factors can influence the timing of when your body enters ketosis, including your age, diet, activity level, and metabolism.

The takeaway.

There are a number of physical changes that your body goes through during a fast, some of which may contribute to the many possible health benefits of fasting.

However, while some people find that fasting works well for their lifestyle, it can cause several side effects and is definitely not a good fit for everyone. Be sure to talk to a doctor or dietitian before trying fasting, especially if you're taking any medications or have underlying health concerns.

Additionally, remember to listen to your body and learn to recognize when it may be time to break your fast.

Rachael Ajmera, MS, RD is a registered dietitian and writer based in San Francisco. She holds a master's degree in Clinical Nutrition from New York University and an undergraduate degree in Dietetics.

Rachael works as a freelance writer and editor for several health and wellness publications. She is passionate about sharing evidence-based information on nutrition and health and breaking down complex topics into content that is engaging and easy to understand.

When she's not writing, Rachael enjoys experimenting with new recipes in the kitchen, reading, gardening, and spending time with her husband and dogs.

20 Sources

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8839325/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5959807/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6471764/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2021.749050/full

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534877/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25911631/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35657690/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8656040/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6472268/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5858534/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5361613/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30172870/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6387456/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31777001/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6314618/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5819235/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30334499/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29315892/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7732631/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8151159/